Not For Trademarks? The truth about NFTs and IP

Collins Dictionary made "NFT" or "non-fungible token" their word of the year for 2021, beating out "crypto," "hybrid working" and "double-vaxxed." We have all heard the initialism, but what exactly does it mean, especially for traditional Intellectual Property (IP) such as trademarks and copyrights?

What is an NFT?

If something is fungible, it is functionally indistinguishable from its equivalent and therefore perfectly interchangeable. This is a fundamental principle of money, meaning that one €5 note from Germany has exactly the same value as five €1 coins from Spain. Another example is pure gold, which can be exchanged for its exact amount of pure gold from another source at no loss or profit.

"Token" in the present context simply refers to the trackable assignment of ownership, updated each time the property changes hands. In effect, NFTs are similar to deeds or certificates of authenticity, only instead of being a physical document, these certificates exist in a blockchain.

A blockchain is a linked series of records (blocks) that are connected cryptographically. What this means is that each time an asset is exchanged, a new record is entered into the data ledger, referring to the record before it and informing that which follows. The outcome is a highly secure history of transfers, resistive to forgery and interference. One cannot change a block in the middle of the chain without invalidating all that follow it.

Most NFTs are created or "minted" on the Ethereum blockchain, a decentralized peer-to-peer network of host computers. Crucially, an NFT transaction does not affect Intellectual Property (IP) rights, though the associated copyright can be bundled with the sale of an NFT if the owner wishes.

All of this is to say that an NFT is a certificate of ownership of a particular digital representation – usually an image, but anything from tweets to the source code for the world wide web can be minted. The all-important detail is that an NFT should not be confused for the underlying work it represents.

Why now?

Although not an invention of lockdown, it is perhaps no coincidence that the market for NFTs exploded while many people were unable to leave their homes. Harvard law professor Rebecca Tushnet references Matt Levine's "Boredom Markets Hypothesis" when she states that "[i]n lockdown, people can't do many of the things they usually do for fun, so they trade intangibles instead. That seems like a good explanation for the rise of NFTs, with a side order of conspicuous consumption: Instead of setting piles of money on fire, you can set piles of money on fire on the blockchain."

It would certainly seem that people had time on their hands and money to burn in 2021, considering some of the most expensive NFTs sold last year:

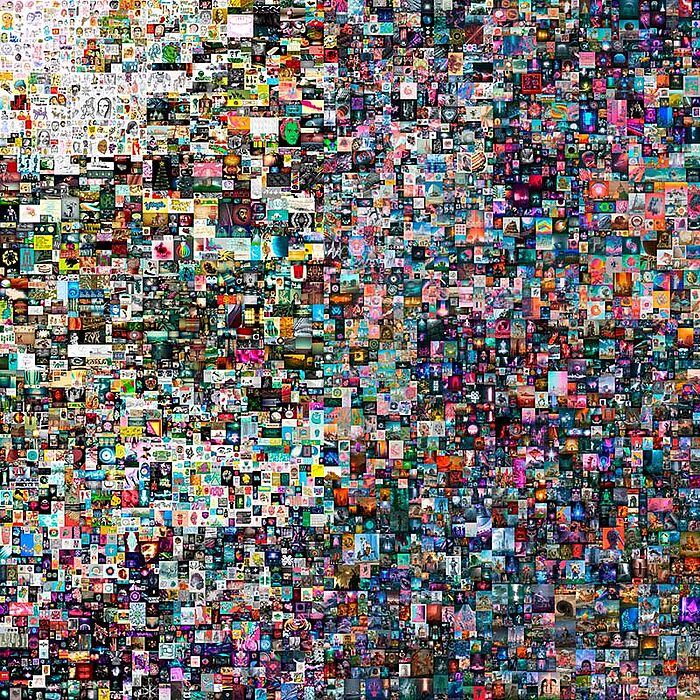

"Everydays: the First 5000 Days" ($69.3 million)

"Human One" ($28.9 million)

"Cryptopunk #7523" ($11.7 million)

Yet, despite the emerging value of this type of digital asset, its precise legal standing and implications are far from clear at this point.

"Everydays: the First 5000 Days" is a collage documenting the artist's daily drawings over a period of more than 13 years. Created by Mike Winkelmann, aka Beeple, the record-breaking artwork was the first NFT sold by auction house Christie's and, to date, the most expensive anywhere (Image source: nytimes.com via Wikipedia)

The legal impact of NFTs

Even though the first NFT – "Quantum" – was minted in May 2014, these commodities are still not formally regulated from legal or IP perspectives. With this paucity of codification and relevant case law, an analysis of the influence of NFTs can only be carried out by applying principles of established law to the core characteristics of NFTs.

As mentioned, one of the most important aspects we can examine is related to copyrights. As an NFT is just a representation of the underlying work and not the work itself, the sale of an NFT does not provide the buyer with the copyright to the work it signifies.

From a legal perspective, this distinction seems clear. Nevertheless, an NFT group called Spice DAO paid for an expensive lesson on this point of law on January 15 this year, splashing out €2.66 million for an NFT depicting the book "Jodorowsky's Dune" in the false belief this conferred them the copyright to the represented book.

On the other hand, in the case of digital artworks explicitly created to be minted as NFTs, the line between underlying work and minted NFT may become extremely thin, almost unnoticeable.

Hermès sues NFT creator

On January 14, 2022, luxury design house Hermès filed a lawsuit against Mason Rothschild with the Southern District Court of New York, citing multiple causes, including trademark infringement and dilution.

Mason Rothschild is a digital artist who has created "METABIRKINS" NFTs featuring the Hermès BIRKIN handbag design. Hermès alleges that the defendant advertises and sells the NFTs on multiple marketplaces under the METABIRKINS name without Hermès' permission and in violation of its trademark rights.

Hermès describes Rothschild as "a digital speculator who is seeking to get rich quick by appropriating the brand METABIRKINS for use in creating, marketing, selling and facilitating the exchange of digital assets known as non-fungible tokens." The plaintiff adds that the defendant's METABIRKINS brand "simply rips of Hermès' famous BIRKIN trademark by adding the generic prefix 'meta' to the famous trademark BIRKIN."

The lawsuit is based upon seven causes of action:

- Trademark infringement (15 U.S. Code § 1114)

- False designations of origin, false descriptions and representations (15 U.S. Code § 1125(a))

- Federal trademark dilution (15 U.S. Co de § 1125(c))

- Cybersquatting under the anticybersquatting consumer protection act (15 U.S. Code § 1125(d))

- Injury to business reputation and dilution (New York General Business Law § 360-1)

- Common law trademark infringement

- Misappropriation and unfair competition under New York Common Law

The novelty of the NFT marketplace means that IP case law has yet to account fully for these assets. If you wish to mint your own NFTs but are unsure of the legal repercussions, it is good to err on the side of originality or seek specialist advice.

On January 17, 2022, Rothschild posted a statement on Instagram in response to Hermès' action. In it, he claimed that "the First Amendment gives [him] the right to make and sell art that depicts Birkin bags, just as it gave Andy Warhol the right to make and sell art depicting Campbell's soup cans."

The future of NFTs

Another ongoing lawsuit on the legal status and derivation of NFTs is that filed by Miramax against director Quentin Tarantino in November 2021. Miramax accuses the well-known director of violating the company's copyrights and trademarks with his NFT collection based on "Pulp Fiction," which he wrote and directed in 1994.

While it may be that the disputed NFTs discussed here experience drastic fluctuations in value due to negative publicity and uncertainty over the courts' decisions, it is highly improbable for these cases to trigger a collapse of the general NFT market. A simple reason for this is that more and more big-name brands are taking their first steps into the NFT realm: Taco Bell, Coca Cola and Nike are just a few. For these companies, the risk of their NFTs becoming the subjects of legal actions is extremely low to zero on account that they own all the IP rights related to the underlying works.

No doubt, IP practitioners, legal analysts and NFT traders alike will be avidly anticipating the decisions from the U.S. courts as these judgments will help determine how NFTs interact with long-standing IP rights such as copyrights and trademarks. Dennemeyer, for one, will be keeping a close watch on all future developments.

Whether you wish to consult the experts before you mint your own NFT or believe your IP rights have been infringed, you can rest assured that the IP professionals at Dennemeyer will lend you all the fruits of their knowledge and experience to stand up for your IP rights.

Filed in

Video games have become some of the biggest names in entertainment. How can digital brands complement their traditional counterparts, and what are the dangers?